Rachel Weeping

I bought the dress for a first date.

Tea-length, navy blue, and decorated in white, beige, and coral polka dots, it’s A-line design accentuated my curves and gave me just enough of a pop to stand apart from the crowd at Neighbors, the Murphy Road bar where I first met Michael for a few drinks, a long conversation, and an even longer goodnight kiss.

The polka dots worked, at least for a little while.

Michael was smart, handsome, and financially responsible. And though he was within reach of paying off his mortgage before turning 40, he did not own hand soap or, from what I observed, a broom. He did, however, play guitar. That helped me overlook the unswept floors, as did his ownership of the Comic Book Bible. The latter also invited me to browse his home library. That was and remains standard practice in my dating game: show me yours, and I’ll show you mine.

His was a lot of Shakespeare:

Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more,

Men were deceivers ever,

One foot in the sea and one on shore,

To one thing constant never:

~Much Ado About Nothing (2.3.64-67)

Just over 400 years later, writers from my musical library drew from one of Sir William’s most well-known comedies to remind us that even with centuries of practice, grown-up love can still be a challenge:

Sigh no more, no more

One foot in sea, one on shore

My heart was never pure

You know me

You know me

~Mumford & Sons, “Sigh No More”

Deceiver? Sometimes.

Never pure? I choose to believe Michael was pure, at least for a little while, and especially during the second and only other vivid memory I have of wearing that polka dot dress.

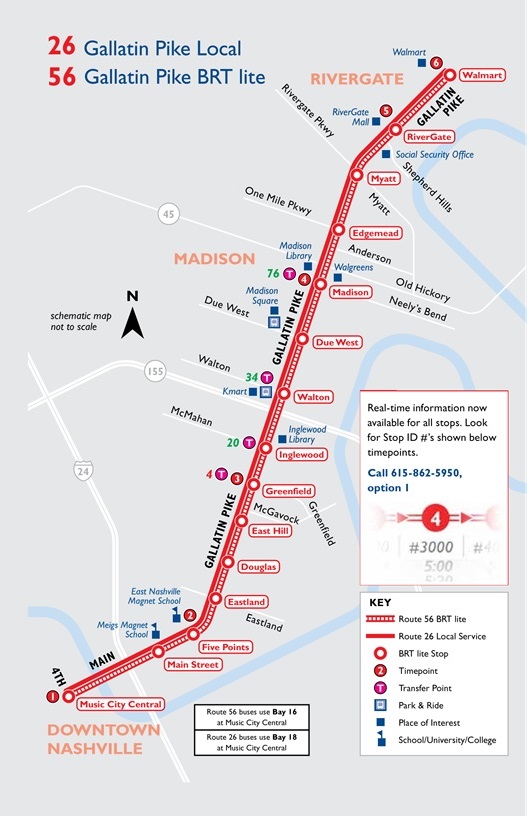

It was a humid, Nashville, July Saturday and rain was coming. I was traveling on the #56 for the first time, heading to the Spring Hill Funeral Home & Cemetery to attend and offer a few words during a funeral for a family I had come to know well. I was especially close to the new mom, a former patient who regularly requested and was regularly open to spontaneous visits during her extended stay in the high risk pregnancy wing at St. Thomas Midtown. The unit quickly became my favorite to visit during my year of chaplaincy. The staff was a small group, and dedicated. And though every day meant working with the possibility of new life or new death, they were always warm and inviting.

Julie was close to my age and carrying twins. She had an older son, whom she both adored and respected, and she would be raising her twins the same way she was raising her pre-teen: on her own.

We clicked immediately. She always wanted to talk religion and she wasn’t afraid to ask the questions often hushed by those in positions of religious authority. She wanted to know why, how, and what if.

So did I.

Julie had a lot of time to think because she spent a lot of time in bed. For her, high-risk meant that movement needed to be rare, short, and on purpose. Her boredom sat in quickly as she was restricted to little more than television, vital signs, and baby monitors. Early in her stay, Julie began learning to make winter hats with a kit provided by the nurses and patient techs from my favorite wing. After all, there would be two more heads to keep warm come winter. They would also take her on wheelchair trips, sometimes to the Serenity Garden on the back side of the hospital for a change of scenery, or to the nursery where her babies would soon be snug as a bug in a rug under heat lamps. Many of those same chauffeurs had helped plan a baby shower in Julie’s room, complete with decorations for her coming twins and cupcakes in pink and blue. So many of us were invested in her pregnancy, especially because it had been with us so long.

While visiting another patient one evening, I received a page that would lead me to Julie. At the time I only knew I had a call to return. As the weekends were a little quieter and generally open to a few more casual conversations, which I thought the page might be, I was in a less stressed state and enjoying the opportunity to catch up with staff when I wrapped up a visit. Along with fewer footsteps and fewer events, however, there were also fewer chaplains. One, to be exact. As the solo spiritual representative in a hospital with hundreds of beds, the page was mine to answer. During the week, it might have been taken by a peer, but it would have made its way to me because Julie was on my chaplain radar and she had given birth.

But one of her twins was dying.

I prayed while I ran. The stairs were faster than the elevator. And as it so often was in that building, my prayer was for reality to be something other than what it was.

No, no, no, no, no. Please, God. No.

I prayed while I scrubbed my hands and cleaned underneath my nails, both protocol for any visitor who entered a space filled with vulnerable babies.

Help me do this. Please, God. Help me do this.

The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit was always quiet. The little ones needed as much rest as possible to try and heal, grow, and breathe on their own. Julie was sitting, surrounded by family, nurses, and a physician there to explain, as gently as possible, that her newborn son would not survive. He had worked so hard to breathe while waiting to be born that the holes in his lungs required a machine to keep him alive on this side of the womb. When the machine had to give 100%, Baby David could not, and would not be able to take in enough breaths or release them into the world on his own, to live. Nothing could have been done differently.

There was no why, how, or what if.

Julie could have as much time as she wanted.

She wanted to take it all.

I have met parents, children, strangers, and friends who have believed they could love someone back to life, that they could hold someone with enough warmth to make a body reverse its journey to whatever it is that comes after here. Any of us in that space would have done so, if the could was more than a hope.

Julie, the one who would have given her own life to save the baby in her arms, instead had to find the strength to let him go. She had to be the one to say, “It’s time,” and cling to tender moments as the ventilator was turned off, tubes were removed, and her son spent a few tiny breaths as a perfect baby, wrapped in blue and held in the love only a parent knows.

When I was asked to share some words during the funeral, I drew from the Psalms:

For you created my inmost being;

you knit me together in my mother’s womb (139:13).

I don’t remember any other words from that day, but I do remember the dress and the rain. Polka dots for a newborn, and tears from the sky for his short life:

A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be consoled,

because they were no more (Matt 2:18).

Rachel wept all morning, leaving the earth soaked in her grief. Her tears flowed into our shoes and washed our feet in sorrow. When she stopped to breathe, just before we made the slow and somber walk to the graveside where Baby David would be buried beside his uncle, she opened the sky to a hopeful blue. And when we all held each other, and when we bowed our heads, we also gave thanks for a life that knew only love as it was made to be.

And when I saw Michael that night, I, too, wept.

And while I wept, Michael, too, was pure.